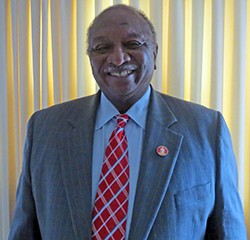

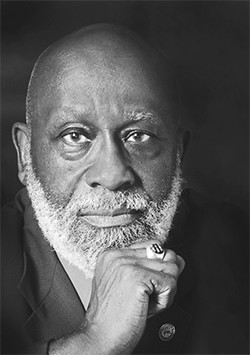

Friend of JCSU - The Honorable John R. Lewis

U.S. Congressman (D-GA 5th District)

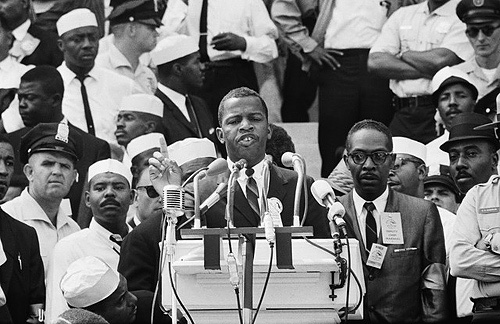

Congressman John Lewis is one of the most noted civil rights leaders of our time. He was a founding member and chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which helped organize the March on Washington. At age 23, Congressman Lewis was one of the keynote speakers at the march.

In April 2013, Johnson C. Smith University presented its prestigious Arch of Triumph Award to Congressman Lewis for his lifetime of sacrifice, leadership and achievement. He accepted the award at the Arch of Triumph Gala on April 20, 2013.

Congressman Lewis’s biography and some of his notable achievements are below:

One of the Civil Rights Movement’s most courageous sons, Congressman John Lewis has dedicated his life to protecting human rights, securing civil liberties, and building what he calls “The Beloved Community” in America. His commitment to promoting the highest of ethical standards and moral principles has earned him the admiration of colleagues from both sides of Congress, as well as distinctions such as “the conscience of the U.S. Congress,” and “…a genuine American hero and moral leader who commands widespread respect in the chamber,” according to Roll Call magazine.

Such designations might have seemed unattainable for the son of sharecroppers born in the 1940s in rural Alabama. But for Lewis, who grew up on his family’s farm outside of Troy, Alabama and as a young boy attended segregated public schools in Pike County, the decision to become a part of the Civil Rights Movement was almost inevitable. Inspired by the activism surrounding the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the words of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., which he heard on radio broadcasts, Lewis reveled in those pivotal moments and since then has remained at the vanguard of progressive social movements and the human rights struggle in the United States.

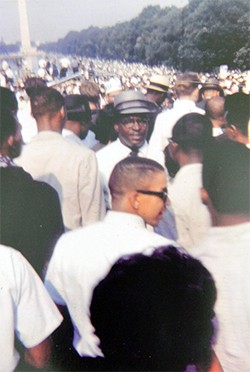

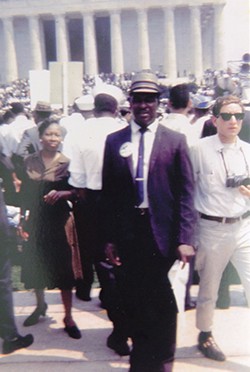

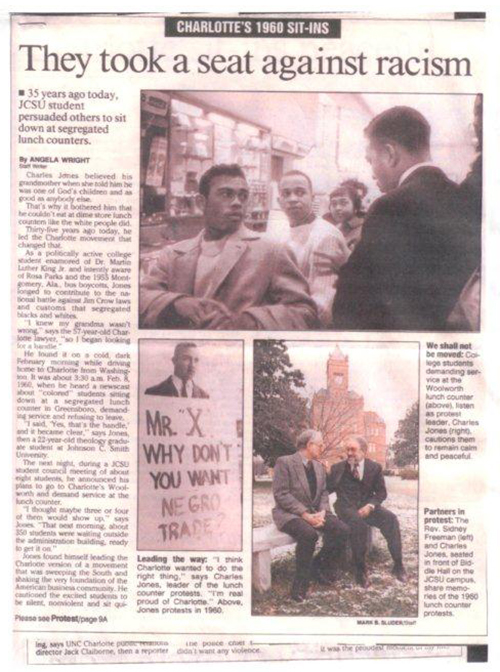

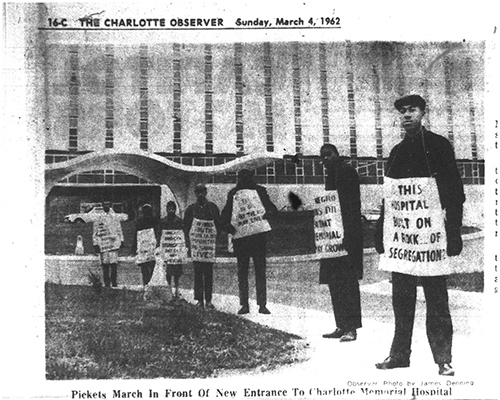

As a student at Fisk University, he organized sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville, and in 1961, participated in the Freedom Rides, which challenged segregation at interstate bus terminals across the South. During the height of the movement, Lewis, dubbed one of the movement’s Big Six leaders, was named Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which he helped form, and at age 23 was a keynote speaker at the historic March on Washington in August 1963.

On March 7, 1965, Lewis, along with notable Civil Rights leader Hosea Williams, helped spearhead one of the most seminal moments of the Civil Rights Movement. The pair intended to lead over 600 peaceful, orderly protestors marching for voting rights across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, but was brutally attacked by Alabama state troopers in a vicious confrontation that became known as “Bloody Sunday.” This senseless cruelty, captured by news broadcasts and in photographs, helped hasten the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Despite more than 40 arrests, physical attacks and serious injuries, Lewis remained devoted to the philosophy of nonviolence. After leaving SNCC in 1966, he went on serve as director of the federal volunteer agency, ACTION, and the Voter Education Project in which he added nearly four million minorities to the voter rolls. Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council in 1981 and to Congress in 1986 where he has since served as U.S. Representative of Georgia’s Fifth Congressional District.

A graduate of Fisk University and American Baptist Theological Seminary, Lewis holds a B.A. in religion and philosophy, as well as over 50 honorary degrees from prestigious colleges and universities across the country, including Morehouse and Spelman colleges, as well as Harvard, Brown, Princeton, Duke, and Johnson C. Smith universities.

The author of a new book entitled Across That Bridge: Life Lessons and a Vision for Change (2012), he is also the recipient of countless awards including the only John F. Kennedy “Profile in Courage Award” for Lifetime Achievement ever granted by the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation, the NAACP Spingarn Medal, and the Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor granted by President Barack Obama.